In his essay, “Ruinous Reflections: On H.C. Andersen’s Ambiguous Position between Romanticism and Modernism,” in H.C. Andersen: Old Problems and New Readings, Jacob Bøggild writes that although Andersen is grounded in Romanticism, “he is striving to move beyond this point of departure,” and he draws on Heinrich Detering’s “phoenix-principle” of Andersen’s poetic system, whereby “poetry will have to consume itself in order to rise in a new shape from the ashes” (75). One important neglected but very significant Modernist writer who takes up this issue and extends it further is Laura (Riding) Jackson, who praised Andersen in several essays, including a difficult and provocative one called, “A Crown for Hans Andersen.”

Elizabeth Friedmann in her authorized biography of Riding, entitled A Mannered Grace (2005) claims of her subject: “Possibly no other woman writer of the twentieth century had comparable impact on the literature of America and England” (vii). Since Friedmann discusses Riding more as a poet and essayist than as a short story writer or novelist, there remains much to think about concerning Riding’s reception of Andersen. In fact, Riding’s short stories have virtually escaped analysis, and except for Deborah Baker, in her earlier biography, In Extremis: The Life of Laura Riding (1993), who devotes a few sentences to Andersen, no one appears to have investigated Riding as a reader of Andersen. For example, neither Joyce Piell Wexler in Laura Riding’s Pursuit of Truth (1979) nor Barbara Adams in The Enemy Self (1990), two standard books on Riding, discuss this matter. In this essay I will show that Andersen played a more significant role in Riding’s formulation of her aesthetics of fiction than has been granted and that at least one of her stories, “The Story-Pig” is a response to Andersen’s tales.

Laura Riding (1901-1991) was a prolific writer of poetry, essays, and fiction during the high modernist years of 1923 to 1939. She abandoned the writing of poetry and fiction at the time of the outbreak of Word War II in order to move on to language studies in her long pursuit of truth. Riding returned to publication in the late 1960s and continued to issue new works and reissue old ones until her death in her ninetieth year. In 1997 her major study, Rational Meaning: A New Foundation for the Definition of Words, was published for the first time, and since then Riding’s place as a writer and thinker has continued to grow. Her novel A Trojan Ending (1937) and her novellas, Lives of Wives (1939), have been reissued by Carcanet Press and Persea Books, presses which continue to promote her literary reputation.

Riding’s most important work of fiction is her volume, Progress of Stories, a very difficult and provocative collection, published in 1935 and reissued by her in 1982 with new commentary, a new story, and earlier stories taken from her prose collections, Experts Are Puzzled (1930) and Anarchism Is Not Enough (1928). The fourth of the five sections of Progress of Stories is an essay of about twenty-eight pages called “A Crown for Hans Andersen” (255-83). It follows seven “Stories of Lives,” two considerably longer “Stories of Ideas,” and four “Nearly True Stories,” while preceding the closing four “More Stories.” Riding also discusses Andersen briefly in the Preface to the volume.

According to Deborah Baker an earlier version of “A Crown for Hans Andersen” appeared unbound in a Seizin Press edition at the end of 1931 (293). Baker states that only six pages are extant, but in them Riding distinguishes her work on stories from her companion Robert Graves’s work on stories. In the published version it is often difficult to understand Riding’s points because she writes in a determinedly cryptic style, and she avoids detailed analysis of Andersen’s stories. One may very well ask whether any stories in Progress of Stories would remind a reader of Andersen’s tales in any way if we did not have her statements of appreciation of Andersen. In this collection only the four “Nearly True Stories” suggest Andersen, since they are clearly more like fairy tales than the “Stories of Lives” and the “Stories of Ideas.” In this third set we find, “The Story-Pig,” “The Playground,” “A Fairy Tale for Older People,” and “A Last Lesson in Geography.” Of these “The Story-Pig” is the only one to evoke Andersen explicitly in any detail, and it is best read as a companion piece to “A Crown for Hans Andersen.”

The essay is divided into five parts. In the first part, Riding praises Andersen for being able to look at life’s situation in the right way. She states:

The right way is to look and not to see too much. You see little like this, but what you see is true. If you close your eyes to the other thing, you see man himself as the here, and a very big here it can look. Look around you and see how big everything looks. And it’s all lies and closed eyes. To tell the truth you have to look at the truth. Hans Andersen looked at the truth and saw small and talked small: this is what his Fairy Tales are. Hans Andersen is looking; he meant what he said for now – in a little while now. (1982: 257)

Alas, no specific fairy tales by Andersen are mentioned at this point to enable us to get a better understanding. However, not all fairy tale writers receive the same praise. The Grimm Brothers seem to be obliquely criticized, presumably because they did not concentrate on what was small and instead asked “What are these secrets?” (256).

In the second section, we leave Andersen entirely, as Riding makes disparaging comments on the stories of King Arthur because of their roots in history. Although she never says so directly, it seems as if she is adhering to the Aristotelian position that we can learn more from imaginative literature than from history because literature is universal. She writes:

Guinevere could not but be false; as the always of the history men can be no real always. There always is a bold human there; and there can no queen rule, no human creature is a queen. A true queen is Queen Story always. (1982: 260-61)

Although King Arthur “may not perhaps wake into the true always, forgetting,” at least “neither will he wake into time again” (263). History, subject to time, pulls story back to earth in a way that keeps the human spirit from being liberated.

Riding returns to Andersen in the third section, where she finally mentions something about his life and work. She recalls his autobiographical writings about his miserable school days, and she praises him as someone who had the noble goal of looking for a place where it would be “no shame for his fancies to show” (268). The stories that interest her are two quest stories from Andersen’s early years: “Den lille Havfrue” [“The Little Mermaid”] and “Paradisets Have” [“The Garden of Eden”]. She claims that what Andersen “took to be the Little Mermaid was his own slow flight towards self-forgetting and thinking only of grace” (266), and the Prince in “The Garden of Eden” is for her a “man on the way to true childhood” (268).

At the beginning of the fourth section, Riding registers fear that stories ruin themselves when they become too long. She praises Boccaccio who showed, presumably with the Decameron, that “a niggling appetite was at least on the safe side” (269). Stories, unfortunately, “grow into novels,” which are “tracts on fate” (270). She claims, “… at the end of every novel there is silence and exhaustion; it has all become a futile pantomime of exaggerated emotiors” (270). We should recall that Andersen wrote no fairy tales longer than “Iisjomfruen” [“The Ice Maiden”]. Riding seems to share Poe’s aesthetics of approval for short tales and poems. She then veers into an attack on eighteenth-century thinkers, who brought about a crisis in sentimentalism, which they foolishly tried to do away with, although it is part of the human psyche. Andersen “woke up in time” and was “born against Napoleon,” who “rose like a plague of vampires from the graves of the dead sentimentalists” to feed on the few sentimentalists still living (272-73). Apparently, Andersen represents the important triumph of the non-clever person over the clever person such as Napoleon.

In the concluding section, Riding makes allusions to several stories by Andersen: “Tommelise” [“Little Thumb”], “Lille Claus og Store Claus” [“Little Claus and Big Claus”], “Grantræet” [“The Fir Tree”], “Metalsvinet’ [“The Bronze Pig”], “Lille Tuk” [“Little Tuck”], and “Holger Danske” [“Holger the Dane”]. More generically she mentions “poor daisies,” “an unhappy old house,” “dead larks,” and “ridiculous storks.” Her comments on “Grantræet” are her clearest:

Then there’s the vain fir-tree, going on from one last year to the next last year, very proud of going on, very proud of standing still. Where’s the end of that? Why, the fir tree withers, and of course stays behind and disappears. But in so far as there’s a story to tell, the fir-tree knew that something was wrong; and in so far as it knew that something was wrong, it knew also that something was right. It made the mistake of thinking, while it grumbled, that the something that was right was its own grumbling – a mistake that is very natural with grumblers. Its own grumbling was the something wrong, of course; and how there came to be any question at all of a something right was that Hans Andersen took pity. “Am I,” he said, “any clearer in my mind than that? Perhaps not. Poor fir-tree, poor me.” (276)

Riding’s evaluation is somewhat peculiar since the fir tree is cut down for a Christmas tree and brought into the house. It is thrown in the attic with the mice after Christmas, and later moved into the yard where it is chopped up into wood. Riding’s stress is not on the pathetic quality of the tree’s death but on the tree’s mistaken view of its place in the world. Since for Riding “any moment is a taste of always” (279), she indirectly calls attention to the tree’s desire to grow up too quickly. At the end of the section, she decides to postpone giving Andersen the golden crown of Queen Story and to go on with “our somewhat inhibited writing” (280) instead. Presumably, if we gave the crown to Andersen now, it would mean that truth is actually being reached through his stories rather than that his stories point to a truth that can be revealed more fully in the future.

A statement from the 1935 Preface clarifies this comment. Here I give the entire paragraph in which he is mentioned:

For a time, that is, we should be telling one another stories or ideas: not altogether unimportant stories, since we were none of us lazy, yet not altogether important, altogether true stories, since we were doing our best but not the best. And we should be gradually feeling that our company was thinning. We should begin to say, ‘In a little while now.’ Some of us would have been saying this privately to ourselves all the time -Hans Christian Andersen among the first. You will see that at the end I have tried to reward his patience, on behalf of us all, with a golden crown, a crown of real gold. For the best time is made out of gold; and all the time that he kept saying to himself ‘In a little while now’ was time of the very best quality. I will not say that it was ‘pure’ – as I would agree with the alchemists that gold was not an ‘element’: no time can be pure. But this was certainly a fast compound, as jealous as gold of its integrity; of sulphurous patience and mercurial hope and salty fear – let whatever he made of it be his secret, as each of us has endured a private magic. (1982: xvii)

Riding validates the notion of “in a while now” as she goes on to say optimistically that in the group of “Nearly True Stories” we are saying to each other “’in a little while now’” (xvii).

In the next paragraph of the Preface, Riding claims that telling the truth to each other “seems to take us back to fairy stories rather than forward to the truth” (xviii). However, the fairy tale forecasts a future revelation of sorts: “’Some time will come a time when in a little while all will be plain’” (xviii). She feels that until we reach the time that we are positive that we are not telling each other lies, fairy tales, despite their apparent unreadiness to the task, will take us further to the pursuit of truth than the actual attempt to speak truth in a direct fashion.

For Deborah Baker, it was in writing her poem Laura and Francisca (1931), about herself, her six-year-old friend Francisca, Robert Graves, and others in Deya, Mallorca, that Riding had discovered herself to be interested in Andersen (293). Although Laura and Francisca is not a fairy-tale poem, it does contain a verse stanza that will remind one of “Den standhaftige Tinsoldat” [“The Steadfast Tin Soldier”], and perhaps the experience of watching a toy boat in a gutter prompted Riding to explore Andersen’s writings. In The Collected Poems of Laura Riding (1980) the lines appear as follows

And so Francisca sails her boat

(I gave it her, she found it by the door)

Down the slow ‘siqui by the wall,

Looking up only not to talk.

She lets it ride, then catches up

By scarcely walking, teasing along

Until the boat at any moment

Might play the fool and drop into the hole.

Enough danger for a short voyage. (1980: 350)

Granted, Andersen’s Tin Soldier’s voyage is much more of a life-and-death affair. Yet the end of Riding’s poem is definitely about death. Baker connects the idea, of the “little ship” with Riding’s life after her suicide attempt. She and Graves made a new start on Mallorca, removing themselves from England (290-300).

I suspect that Riding’s interest in fairy tales also grew from her exposure to Graves’s children from his first marriage. In Four Unposted Letters to Catherine (1930, republished in 1993), Riding writes to Catherine Graves about childhood:

The good thing about children is that if no-one interferes with them they do stop to think about themselves. Childhood is the time when people should be bothered with nothing but themselves. After childhood there is a time between childhood and grown-up-hood called adolescence just before you begin frequently knowing everything about everything. (1993: 14)

Here Riding is annoyed that adults intervene and push children along so that they move on to “really start doing things, that is, before they have finished with knowing about themselves” (14). As a consequence, there are far too many adults who have never stopped to discover themselves (14-15). Children should be permitted to take as long as it needs for them to learn everything about themselves. Yet, children should not sit around and do nothing. They can be given a lot of work to do, since they will be doing it as if it were play (17). Since these reflections were written in the year before Riding made her discovery of Andersen, one can only speculate that she found in Andersen’s high evaluation of childhood a motif in his work pleasing to her.

Riding, under the pseudonym of Madeline Vera, mentions Andersen briefly in the short essay preceding her four translations from George Sand’s Contes d’une grand-mère, which appeared the year after Progress of Stories in the second [June 1936] issue of the journal Epilogue: A Critical Summary (243-49), now reprinted in Essays from ‘Epilogue’ 1935-1937, edited by Mark Jacobs (2001: 157-62). In introducing Sand’s stories, “The Talking Oak,” “What the Flowers Say,” “The Red-Hammer,” and “The Dust-Fairy,” Riding points out how these stories differ from Andersen’s:

The vision of a future in which ‘Reason, Science, and Goodness will reign’ is merely a smiling answer to the child’s prudish complaint that animals should be ‘destined to enrich the earth as manure’: an assurance that it is really all right, ultimately. Hans Andersen’s ‘all right, ultimately,’ was prayerful; he longed for a redemption of the mortal little in the immortal large, and his method was an artless exhortation of the large on behalf of the little, rather than a stern lessoning of the little in littleness. In so far as it is possible to compare him with George Sand he is a religionist preoccupied with universal happiness, she a moralist dwelling on the homely happiness within individual control. It may seem strange to think of George Sand like this; but her children’s tales force us to recognize the private account of sobriety behind her work (2001: 158-59)

Riding also had a moment when she was “a religionist preoccupied with universal happiness.”

In the special issue of Chelsea 69 (2000), called The Sufficient Difference: A Centenary Celebration of Eaura (Riding) Jackson, we find a fragment, “The Serious Angels: A True Story,” called by guest editor Elizabeth Friedmann “An Unfinished Story for Children.” Here Riding states, “… I consider souls and angels to be things like each other; having a soul and having an angel, or being a soul and being an angel come very close.” Riding declares that she has made her soul or angel “my partner in my telling of this story” (2000: 22). Here we sense Riding’s concern for mystery, something she does not want us to confuse with myth.

We ind a few comments on Andersen, children, and fairy tales in the same collection. “A Little Essay,” dated August 1986, opens as follows:

I have long felt uncomfortable about ‘Literature for Children’. The ‘fairy tale’ and the rhymes of Mother Goose, in their sprightliness, are the traditional models for the spirit of this literature. Modern enlightenment-concern stiffens the spirit – endeavors to stiffen it with moral instruction touching on problems social and political not previously judged part of what children should take into their consciousness’s stride. (2000: 15)

Here as in the letter to Catherine of 1930, Riding again registers anxiety about adults’ desires to push children into adulthood. The adults are actually trying to get the children to enter into the confused state which they already occupy. Adults “are the ones who do not know whether they are adult or not; their advanced ideas about children mirror their own double identity as themselves partly n the child-state, partly not fully matured adults” (2000: 15). In a supplementary paragraph from September 1987, Riding states that she should once again mention Andersen, since “I think that his sense of story was a spiritually capacious and clear one: that child and adult consciousness met in his stories in friendly grace, not sentimental confusion’ (16).

In “Poetry and Mystery,” also in Chelsea 69, she makes a statement that perhaps shows indirectly her reason for an appreciation of Andersen as a “spiritually capacious” writer. She claims that in the

…] late modern era … the very idea of the mysterious began to fade from the processes of poetic conception. There grows an impatience with the mysterious, that which is of the nature of the not yet understood (not of the not-understood as the not-understandable). Instead of mystery, an uncomprehended element of reality, unbreached area of experience, there is posited an elusive area of the intelligence itself. The poetic mind becomes the object of poetic transcendence. The poet-self becomes a replacement of the mystery element. (2000: 34)

In addition to this obsession with the human mind Riding finds in this period a “preoccupation with myth” (35) which moves in the opposite direction from the appropriate examination of mystery (35). In other essays, she will heartily condemn T.S. Eliot as a purveyor of this kind of writing.

In “Creating Criticism: An Introduction to Anarchism Is Not Enough,” her preface to her new edition of Riding’s Anarchism Is Not Enough, Lisa Samuels presents Riding as an idealist, what I would call a Kantian:

[Poetry] gestures toward the gift of mortality, toward the ultimate “uselessness” of individuals, and therefore toward the perfect means of their existence. Poetry, more than any other human creation, can engage this “unreal” as long as it is written within the realm of expenditure, or what Riding calls “designed waste.” The true poetic word is an unreal thing made by an unreal individual, serving no tradition of reality. And poetry is a realm of engaging with unknowables, not an historical accumulation of improving points of view. (2001: xix)

In short, Samuels claims that “Like the Romantics – or like the Blakean and Byronic strain of Romanticism – Riding pays the price of invoking a project of impossibility” (xxi). She is looking for Romantic access to transcendence but suspicious that there is no way out of the distorting strategies of Modernist mythmaking. Thus we come back again to the perspective on Andersen’s place between Romanticism and Modernism.

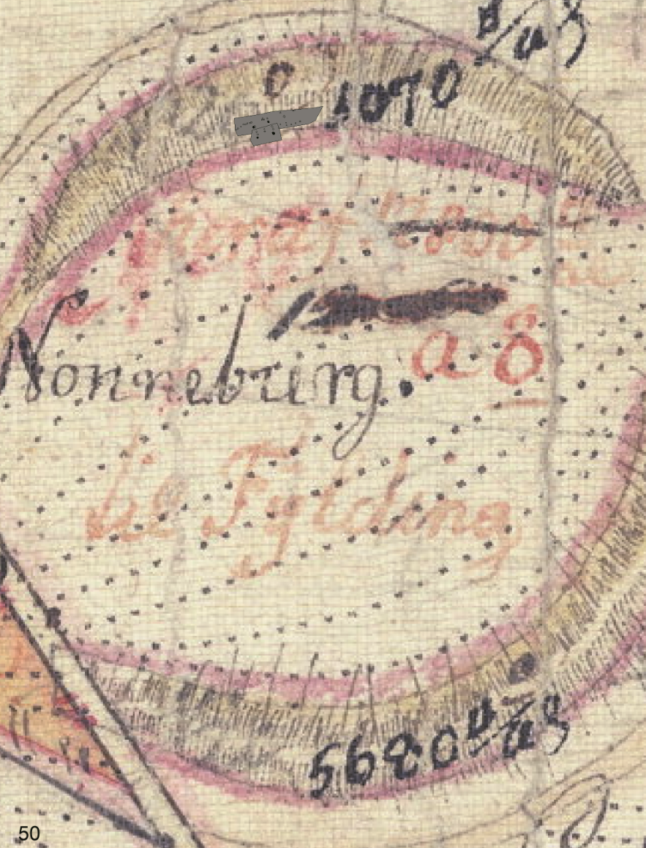

Turning now to critical commentary on Andersen, we see that all three articles devoted to detailed analyses of “Metalsvinet” have in some way stressed its strong Romantic content with the nighttime journey on the pig seen as a symbol of transcendence. Inge Lise Rasmussen Pin’s main concern is the transformation of Andersen’s experiences in Florence in 1833, 1834, and 1840, recounted in his diary entries and their transformation into the story in its first form in his travelogue En Digters Bazar [A Poet’s Bazaar] and later into its final form among his stories. She associates the boy/artist who dies young with the Odense artist Wilhelm Bendz, who died on his first trip to Italy in 1832 (13). Elsa Klange examines the symbols in the story, sometimes from a Freudian perspective. For Klange, life with the bourgeois craftsman, the glover, cuts off the boy’s artistic inclinations, which had been promoted by his journey to places of artistic inspiration with the pig at night (38). Johan L. Tonnesson is more concerned with the structure of the story than with the symbols. For him the structure suggests that art, Eros, and the divine are all mutually supportive (14).

As Bøggild points out, some stories by Andersen, such as “Psychen” [“Psyche”] are more questioning of Romanticism and more anticipatory of Modernism than others. Riding’s “The Story-Pig” addresses this questioning side of Andersen, even though its direct references are more reminiscent of Andersen’s Romanticism: the little match girl (172), the Sandman (175), red slippers (178), Little Claus (179), a brave tin soldier (179), a rose-elf (179), the Snow Queen, Gerda, and a robber girl (181), and a nightingale (181).

Riding works a stunning reversal on the situation in Andersen’s “Metalsvinet.” Whereas in Andersen’s story, the metal pig takes the boy at night to artistic inspiration by exposing him to art, in Riding’s story the motionless pig is finally freed by the actions of the King and Queen, who are aspects of Hans, the doorman, and Rosa, the maid. In “The Metal Pig” the pig frees the boy through its nocturnal adventures, be they magical or dream-induced. In “The Story-Pig” it is the surrealistic nocturnal lives of Hans and Rosa that allow the pig to escape from the mantelpiece of the Hotel Moon.

It is very difficult to describe the action of “The Story-Pig.” Despite its confusing aspects, it is for this reader by far the most impressive of the stories in Progress of Stories. The story has very little action and even less plot. It can be divided into two sections, the first part, in which the pig is stuck in the hotel (167-78) and the second part, which presents the chief event, the night stroll of the King and Queen, which allows for the pig’s escape and the scandalous aftermath (178-86). Alternatively, one could think of the story as two situations, with a minimalist but causal event which separates them.

Andersen’s story is set up to feature a set of dichotomies, whereas Riding’s story foregrounds a series of three contrasting states or situations. In “Metalsvinet,” as all the critics of the story agree, Andersen is contrasting the work of the craftsman and the work of the artist, and praising the higher insight and adventurousness of the artist. Similarly, the artist is associated with dream, whereas the craftsman is associated with reality. Finally, the craftsman may live a long life, but the long life of the artist is usually his immortality, and, as in the case of the street urchin who becomes an artist, the artist dies early. The details of his life are vaguely remembered when the artworks, the proofs of immortality, are appreciated.

The “Metalsvinet” is one of Andersen’s stories that fits well into a typical Romantic paradigm. The transcendent is not to be found in everyday life, and the person with access to this transcendence is the artist. Whereas Riding’s “The Story-Pig” is also about access to transcendence, art is not the form in which that transcendence appears. Instead, art is located on an intermediate level between the world of everyday appearance and the world of inaccessible truth. This is the first of the triangulated situations in her story. The world of story represented by the pig is preferable to the world of everyday appearances, but it should not be mistaken as the embodiment of truth. Whereas Andersen contrasts dream with reality, Riding would have us consider banal reality as today, the story as the promise of tomorrow, and truth as the unattainable ever-after. Furthermore, it makes little sense to think of Hans and Rosa as characters who die to earthly life, since the story concerns the escape of the King and Queen, that is, the true aspects, from Hans and Rosa, leaving behind sorrier versions of the doorman and the maid as a result.

Although Ridings responds to the story, she does not rewrite the plot directly At the beginning of “Metalsvinet,” when a porter drives a poor boy away from the Ducal gardens in Florence on a winter night, he goes to a famous landmark, the sculpture of the pig, and climbs on its back. At midnight it takes him on a journey. They go to see the Duke’s statue in the Piazza del Granduca, and then to the old Town Hall (Palazzo Vecchio), where Michelangelo’s David and Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus can be admired. They also see Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabines in the Loggia dei Lanzi, and the Venus de’ Medici in the Uffizi. Inside the Museum, the boy is struck by two paintings of Venus by Titian (now in Uffizi Room 28: Venus with Cupid [1548] and Venus of Urbino [1538]), and a painting of Christ descending into Hell by Agnolo Bronzino. The pig, however, cannot take the boy into a church, and so the boy has to enter Santa Croce alone. Here he sees the tombs of great artists, such as Michelangelo and Dante.

In the morning, the boy finds himself half slipping off of the metal pig’s back at the Porta Rossa. He has to go and face his slatternly mother’s wrath for coming home with nothing. She attacks him with a pot, and he flees to Michelangelo’s tomb, where he is found by Father Giuseppe, who arranges for him to be taken in by a glover and his wife as a kind of servant/apprentice. He becomes interested in drawing when he assists a painter, who lives nearby. However, the boy’s life is changed when the glover’s wife’s dog follows him on a walk to find some emotional relief with the bronze pig. The mistress of the house assumes that he has stolen the dog. Later he ties up the dog to sketch it, and this is the last straw for the boy’s mistress.

We read that the painter came up the stairs, and then suddenly there is a break in the story line. We are told that it is now 1834 and there is an exhibition of two paintings at the Academy of Arts in Florence: one of a boy, drawing a dog, and a larger picture of a boy, fast asleep by the metal pig. The latter has a gilt frame with laurel and a black ribbon because the young painter had just died. The narrative leap from the beginning of the boy’s artistic career to the posthumous exhibit of his paintings suggests (although it is not completely clear) that the fame of the painter is only posthumous. Laboring in obscurity has been his lot in life. The most intriguing part of the story is the final section, where the action has stopped. The first painting presents the moment when his painting career began, whereas the second is a representation of the moment of inspiration that led to the beginning of his painting career.

Handskemagerdrengen var bleven en stor Maler! det viste dette Billed, det viste især det større ved Siden; her var kun een eneste Figur, en pjaltet, deilig Dreng, der sad og sov paa Gaden, han hældede sig op til Metalsvinet i Gaden porta rossa. Alle Beskuerne kjendte Stedet. Barnets Arme hvilede paa Svinets Hoved; den Lille sov saa trygt, Lampen ved Madonnabilledet kastede et stærkt, effectfuldt Lys paa Barnets blege, herlige Ansigt. Det var et prægtigt Maleri; en stor, forgyldt Ramme omgav det, og paa Hjørnet af Rammen var hængt en Laurbærkrands, men mellem de grønne Blade snoede sig et sort Baand, et langt Sørgeflor hang ned derfra. –

Den unge Kunstner var i disse Dage – død! (1: 193)

[The glover’s boy had become a great painter, as the picture clearly showed. But the larger picture was a still greater proof of his genius. There was just a single figure in it, a handsome ragged boy leaning, fast asleep, against the metal pig of the Via Porta Rossa. All the spectators knew that spot very well. The child’s arm rested on the pig’s head, and he slept sweetly, with the lamp before the near-by Madonna throwing a strong light on his pale, handsome face. It was a beautiful picture. A large gilt frame surrounded it, and a wreath of laurel was fastened to one corner of it; but a black ribbon was entwined in the green leaves, and long, black streamers hung down from it. The young painter had just died!] (1948: 29)

Together the Madonna’s light and the Greek laurel wreath symbolize the union of Greek and Christian ideals characteristic of an important part of the Florentine Renaissance, with which Andersen is in sympathy.

Riding, in contrast to Andersen, has no artist in her story. Her story is about stories but not about a great story teller. The Story-Pig creates the stories. On the hotel mantelpiece it “held its mouth wide open and gorged itself on the idle thoughts of the guests,” which “turned to stories in the pig’s shiny belly” (167). What the people told each other were “things to increase their self-respect – not exactly lies, but not exactly the truth: things to make the world seem a nice place to live in” (168). Left alone, the pig would “go on all night telling over to itself all the stories that it had heard” (169). During the day Hans would stand at the door and listen to the stories, and Rose, the maid, would clean the room. The pig at night was “a sentimentalist, by day it was a snob” – like the people in the hotel (170). Riding does not explain why, but presumably with nightfall the hotel guests became more ruminative and nostalgic about the events of their lives and opened up more to contact with others. However, the pig was not the only important object in the room. There was a tall basket into which people threw unwanted items, such as discarded luggage. Surreptitiously, Rose would take these items up to the attic where she slept.

At this point (171), the story becomes much more confusing. We learn that Hans is the Sandman who visits Rose at night, and as the Sandman he helped her see herself as she actually was.

At night she stepped into the beautiful picture that hung over the Storypig, and down the stream of her true self she floated, a very invisible queen in a very visible ship, on her way toward the place where she would be visible only to those who knew how to see her as a queen and speak to her as a queen. (171)

Only at night is Rose able to become the “gold and silver Queen” (173). The transcendent in the human being takes over Rose and Hans at night, and this transcendence is not made accessible through the form of stories nor through earthly beauty (such as Andersen’s beauty of the images of the Madonna and of Venus), as Riding makes clear.

Transcendence in Riding’s world is more the truthful than the good or the beautiful. At this point the narrator tells us:

From the grain of truth in a flower the most wonderful tales took their beginning. But where did tales lead to? Back to the tea-pot, back to the Story-pig: in fact, was anyone the wiser for a tale, no matter how much better he might feel for acknowledging to himself that things were not altogether what they seemed? (175-76)

Tales are consolations for the human condition of being unable to reach the truth, and they should not be glamorized for being more than that.

As in Andersen’s tales, objects take on a special life at night. Here in Riding’s story the items of discarded luggage are no exception.

They had seen the Queen; they were inside the picture; they were behind the picture, on the reverse side, in another kind of to-day. And there were no yesterdays to that to-day. All the other to-days were not merely long ago; one could not credit them with having been at all, except in the minds of the people who had lived in them and made finished pictures of them. These pictures were only pictures of the real picture, which was not a picture at all, but the real world itself; and here everything looked like what it really was, not, as in everyday pictures, like what they seemed to people who kept their eyes tight shut … lest what they saw should shock their vanity … (175-76)

This passage, in which Riding recalls Plato’s suspicion of art in the Republic, revises Andersen’s nighttime world, since the nighttime world is still at a distance from the real not an incarnation of the real.

At this point the limited action in the story begins, as Rose/Queen takes her walking stick and puts on her red slippers and goes out with Hans/King into the road that leads to the elfin hillock (178). She is followed part of the way by a rose-elf (179-80). However, this nighttime world is not to be considered the world of enchantment or magic.

Had the magic been that crafty meddling with the rules of the game that never succeeds but it fails, then she would have been only the fierce, false Snow Queen of intellectuality, and Rose would not have been the same as the Queen, impossibly the same, but any fine girl -Gerda, for example. And Gerda would have been half any fine girl, and half the terrible robber girl … (181)

Just as art does not give us access to the transcendent, neither does magic or nature – “the nightingale singing – taking advantage of effects” (181).

However, when Rose and Hans arrive home, she takes off her slippers, and he says “Boo! ” at the Story-pig’s snout. Then the pig “skipped out of the window and up to the moon and into it – at which the moon promptly set” (182). The King suddenly disappears as this happens, leaving the Queen alone. The next morning, Rose is found asleep on the couch in a faint and has to be taken upstairs, and Hans becomes “impolite and free with the guests” (184).

These events are considered scandalous, but even more importantly, something happens to the painting over the departed pig.

And what of the picture over the missing pig? For it had been found turned to the wall! And when it was turned back it was unmistakably faded, as if someone had scrubbed it with soap and water to wash away the surface and get through to a better picture underneath, and failed, and turned it to the wall in disgust – that so beautiful picture of the view from the hotel in moonlight, looking across the Valley of a Thousand Turns towards the sea, which seemed to say “Slowly, slowly!” as it slowly bore the visible ship to an invisible Somewhere. For whom was the picture not good enough? It had been painted by one of the most famous artists in the world … (183)

The hotel had received the painting as a gift from the artist himself when he was allowed to stay there for free because of his reputation. Thus unlike the two paintings at the end of Andersen’s story, this picture becomes part in a commercial exchange which people do not want exposed as such. We do not know who tried to get behind this Romantic landscape to the “truth,” in a literal minded way, by trying to find what lay beneath the painting. Whoever tried, apparently hid this unsuccessful attempt to find the truth behind appearance.

So the story ends with the pig’s disappearance, the turning of the landscape picture to the wall, and the return of Hans and Rose to their boring lives. In addition, the picture is replaced with “a vase of fresh roses – always fresh, but always fading” (183), always already in the process of dying. Riding implies that the moment of transcendence is unique and fleeting – just this one moonlit walk. The dismissal of the pig shows that when we can somehow gain access to truth there will be no more need for story (art), as represented by the pig and the painting. However, how it can happen, we do not know. We can anticipate the great outcome when it does happen, but there is no prescription for how we can turn ourselves into the King and Queen. The walk is mysterious like the night excursion of the pig and the boy in Andersen’s tale, and, as in the earlier story, no explanation for it is possible. However, in Andersen’s tale we do not expect it to be logically motivated. In Riding’s more modern, realistic story, the absence of such motivation feels more frustrating, although the narrative technique is very similar.

As Riding does not indicate in Progress of Stories the composition dates of each piece, it is not possible to tell whether “The Story-Pig” was written after “A Crown for Hans Andersen” in order to qualify her initial praise for Andersen. It is hard to say whether Riding’s appreciation for Andersen fell away, since after 1939 she stopped writing fiction. However, there is no reason to think that at this point Riding was any more irritated by Andersen than by anyone else. In fact, the pieces collected in the recent Chelsea volume seem to indicate a lasting appreciation for Andersen rather than a temporary interest in him.

Andersen appealed to Riding in part because she was predisposed to fairy tales and to the Romantic movement. However, she never engages in the kind of comparison which would help us to distinguish his merits over many other Romantic fairy tale writers, Ludwig Tieck, for example. The brief comparison of Andersen to George Sand is all we have along these lines. Furthermore, Riding does not stress the didactic side of Andersen, evident in a story such as “De røde Skoe” [“The Red Shoes”] and she is capable of bending a story to her own views, as we see in her discussion of “Grantræet”

More inspiration than model, Andersen helped Riding as she worked through her project on truth-telling, which dominated her whole creative life. She acknowledged her appreciation of him in “A Crown for Hans Andersen,” but in “The Story-Pig” she critiques the Romantic cult of the artist to which he often subscribes. As Bøggild asks in reference to the end of ’’Psychen,” is Andersen suggesting that the ’’mysterious entity that we all possess, a soul fashioned in the image of God is a promise of eternal life, or is this innermost soul rather concealed, invisible, and therefore unrepresentable?” (94). Although Riding’s “The Story-Pig” does not deal with the soul, it certainly deals with the possibility of representation of the transcendent, and it uses throughout convoluted syntax, which Bøggild finds characteristic of “Psychen” (94). Thus Riding’s rewriting of “Metalsvinet” should not be labeled as either a simple homage or a critique of Andersen, but a complicated engagement with his poetics.